A Doctor in the Family: ‘Anything Less is Failure’

Iraqi students have little choice when it comes to their careers. Ali Hakem is trying to give young people the freedom to determine their future

There’s a price to pay for being a good student in Iraq. Like other countries across the Middle East, the education system steers top students towards certain degrees, determining their career paths based on performance and prospects rather than passion for the subject. Students with top grades study medicine, while those who miss the mark do engineering or join the military.

These students will be assured a job when they graduate and command a respectable salary. Those who fall short of the top grades are often made to re-sit the year by ambitious parents determined to have a doctor in the family. Some will sell their house or car to afford private tutors and ensure their children get into medical school.

“It’s every student’s goal in life to become a doctor because they are considered first-class citizens here… anything less is seen as a failure,” says Ali Hakem, who turned his back on traditional learning when the system refused to sanction his career plans. “Teachers, parents, society – they all said medicine, but I hated it. I wanted to study physical education and pursue a career in sports.”

Hakem retaliated by leaving school and spent eight years working with NGOs, learning on the ground and engaging with different social issues. He also wrote three books and became a social and human rights activist, conducting workshops across the Arab world. But little has changed for students since Hakem left school, and now he wants to support young people facing the same scripted career paths that forced him to reject traditional learning altogether.

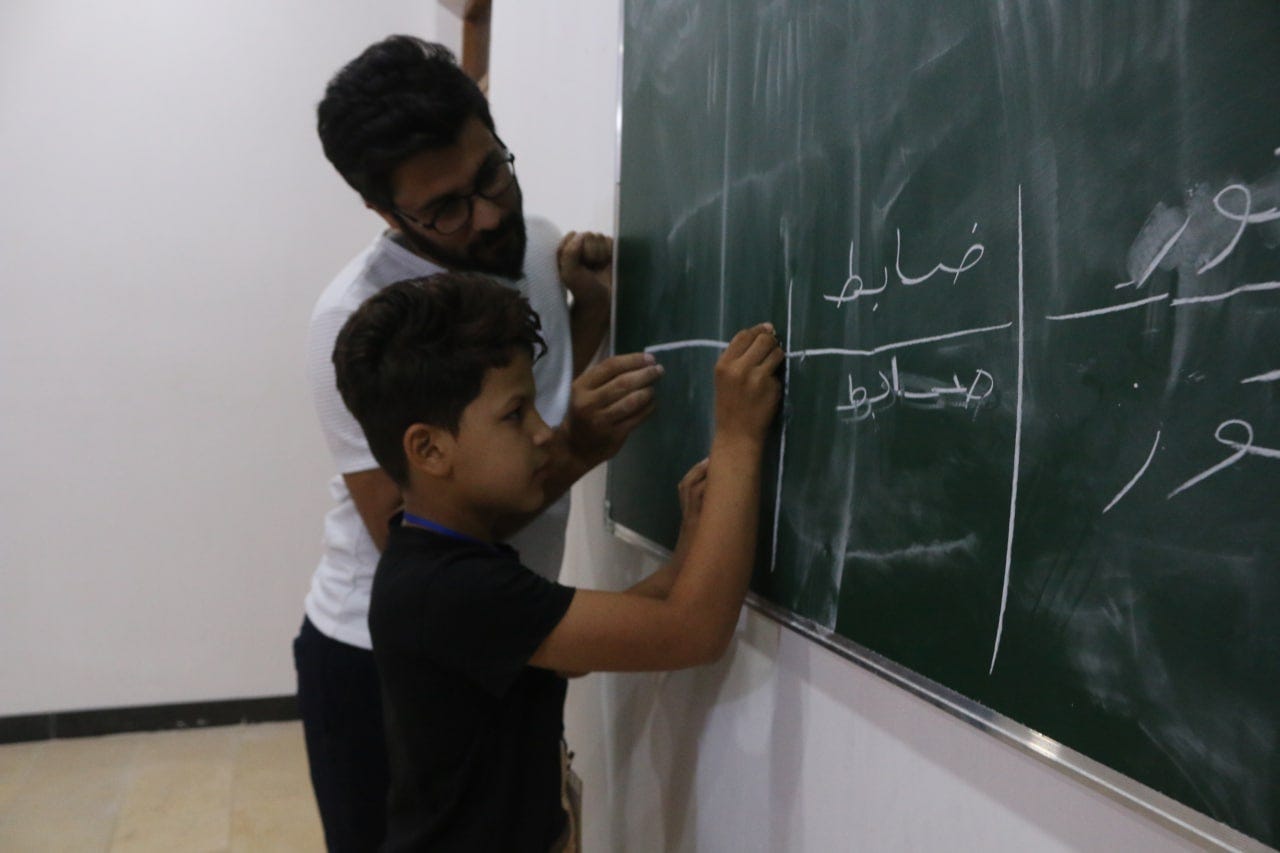

“I want to help others follow their passion and discover what that is,” says Hakem, who launched Education Revolution in 2022 to challenge the rigidity of a system that denies young people a say over their future. The platform runs courses in unorthodox subjects that don’t appear on the national curriculum, including Democracy and Dialogue, Environmental Protection and Volunteering.

Many students don’t even realize they have been conditioned, Hakem says, they are just pursuing the path laid down for them. Those who don’t achieve the highest grades are forced to accept second-class status, regardless of the talents they might have outside of the mainstream. “The humanities subjects - arts, sports, administration, economics, civil society, law, philosophy - most of these majors are considered worthless,” he adds.

Hakem conducted an experiment in one of his classes, asking students what they wanted to be when they grew up. Out of 14, five said army officers, the rest, doctors. During subsequent sessions, he invited them to explore their interests and introduced the idea that these could inform their future career choices. After this, the answers were more wide-ranging.

“There was everything from airline pilots and football players to designers and engineers. I managed to change the mindset of these students, hoping that they will carry these ideas home to their parents and influence society in the long run,” Hakem says.

He’s already seen the impact on several students, including a 13-year-old boy who harbored dreams of being a football match analyst. Hakem called in a favor and arranged for the teenager to do work experience at a local television station, then analyze a match on live TV. “He’s now known as Iraq’s youngest match commentator and his parents are incredibly proud. He’s shown that he can still achieve that social status by doing what he loves.”

The sessions target three age categories, including under-14s, 14 to 18 years old and young adults. Other courses taught by Education Revolution include Social Media, Volunteering, Art and Sports, but to an extent, the students choose what they learn, identifying the issues they wish to examine each time. “The first goal is to provide a safe space for students to express their passions and then help them develop those passions and reach their goals,” Hakem says.

Teaching methods also deviate from traditional approaches in Iraq. Instead of rote learning based on repetition and memorization, Hakem’s students will watch a documentary and then discuss the issues explored or examine social media posts and consider the arguments raised. Emphasis is placed on tackling the prevailing issues of the day. If someone asks about the spread of terrorism online, then homework might be preparing a post that counters violent extremism. Sessions also highlight the value of volunteering, says Hakem, who tasks students with activities like tree planting and litter collection to instill a sense of social responsibility.

With an Innovation Hub grant from Ideas Beyond Borders, he has equipped a proper classroom and expanded the sessions to reach more students. “Young people in Iraq face pre-determined career paths thanks to an education system that decides their futures for them,” says Faisal Al Mutar, President of Ideas Beyond Borders. “They are missing the chance to pursue their interests and excel elsewhere, denying Iraqi society the benefits of a diverse talent base.”

Hakem is optimistic about the potential of these classes to make an impact by giving young people the license to shape their own lives. Now some parents are starting to take note. When he held an exercise to visualize the effects of the education system in Iraq - asking students to draw a prison and then list their passions outside the walls - it gained widespread coverage in media outlets. “When parents saw this, it had an impact. A lot of people wrote in and asked the government to change the system,” Hakem says. “So in that sense it worked.”