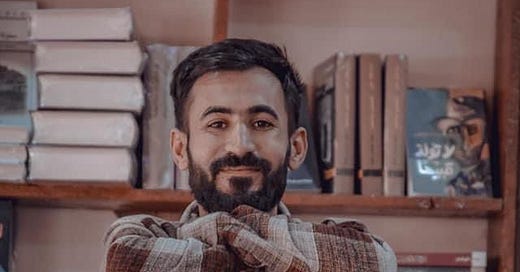

‘Books gave me strength’ – Sinjar’s Lone Librarian

Yazidis have little access to books in Sinjar but one man is carving out a space for culture in his war-ravaged heartland

It was boredom that made life in the camp unbearable, worse even than the squalid conditions. They were safe here, but that was all. Days dragged by, slow and relentless, with little distraction from the grim surroundings. No one knew what would come next. ISIS had rampaged through Sinjar, forcing the Yazidis to flee, and Kamiran Khalaf was among them - the lucky ones who escaped genocide only to end up here, in this no man’s land behind coiled wire and high grey walls.

He was meant to be at university, studying to complete his degree; instead, he was stuck, unable to work or study or pursue any kind of dream. “Living in the camp was hell,” says Khalaf, describing the grinding struggle to meet basic needs and the mental turmoil that made every moment more arduous. The only consolation was books, so he read constantly, trying to escape the emptiness of living in exile. “For me having books was a lifeline, even when I lost education I could still gain culture and experience by reading,” Khalaf says.

Access to books and education was extremely limited in the camp, so in 2015 Khalaf turned his tent into a library, allowing people to borrow his books for free. It was an immediate success. People flocked to his tent, particularly youth looking to reignite their studies or escape the drudgery of camp life. “Books gave me the strength to overcome stress and anxiety. They made me a better person,” Khalaf says.

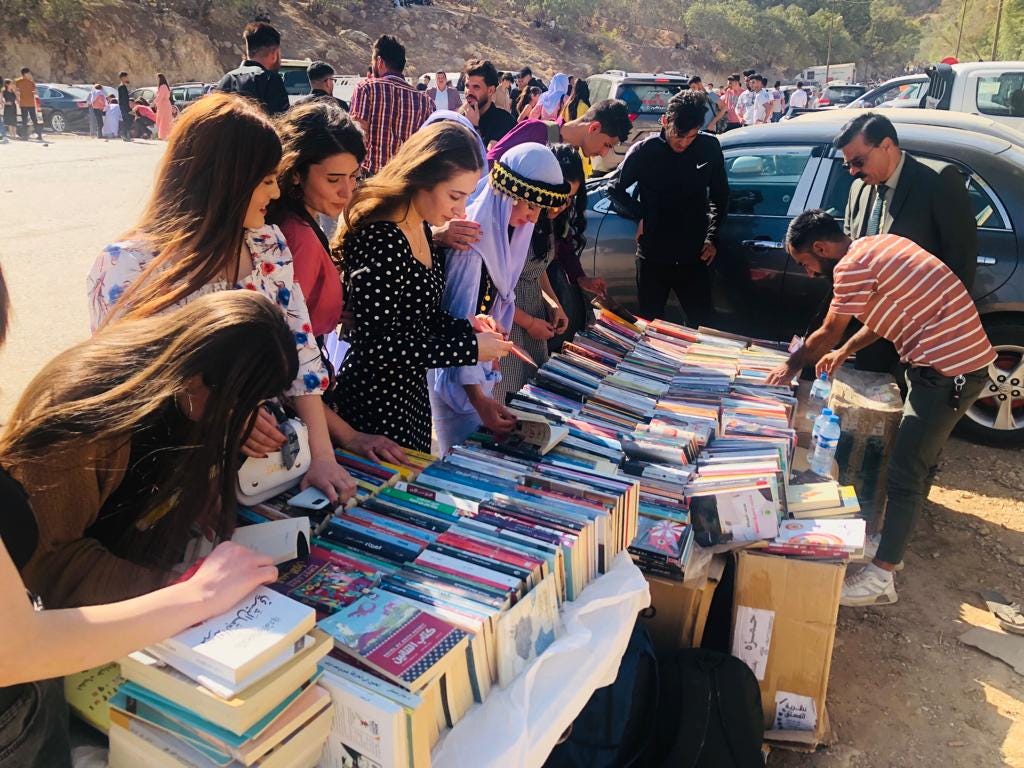

Over time he amassed more than 600 volumes, building on his collection with donations from elsewhere. When he returned to Sinjar in 2017, Khalaf decided to establish a permanent lending library and book shop, hoping to reignite an interest in reading and restore a bit of culture to his ransacked land. “This area was once well-educated, people used to be very interested in books, but since war erupted in 2013 that deteriorated. With the displacement of so many people we lost access to the tools of education,” he says.

Sinjar has been caught in multiple conflicts since ISIS invaded the region in 2014. When the militants were expelled in late-2015 they left a power vacuum that has been filled by other armed factions, all fighting for control over this bitterly contested piece of land, which occupies a strategic position near the Syrian border in northern Iraq. Because of this, and insufficient funding from the federal government in Baghdad, reconstruction in the wake of war has been painfully slow, with public services and basic amenities barely functioning. Around 70 percent of Sinjar’s Yazidi-majority population remains displaced, with little incentive to return while their homeland is trapped in turmoil.

Khalaf was among the few Yazidis that returned to Sinjar after ISIS was defeated in 2017. Almost immediately he set about finding a space for his books, renting land on the edge of a park in the center of the city. He opened the Orshina library in early 2018 and gradually added to a collection that now numbers 6,000 volumes, filling the shelves with novels, poetry, politics and philosophy as well as books on learning English and self-improvement, which are always a popular choice, he says.

But despite enthusiasm from his supporters, it hasn’t been easy. “When I first had the idea, people actually opposed it and said would be impossible to achieve, but now that they are starting to see the change I have achieved,” Khalaf says. “We have become a cultural monument in the city; any newcomers here are immediately brought by locals to see it and show that we do have culture in this city.”

Nevertheless, he faces constant harassment from political parties who see his library and its access to ideas as a threat to their agendas. “They don’t want people being educated, they want to keep them on a leash, under their control,” Khalaf says. Last year, he was forced to close the library for six months due to political pressure but eventually, he was able to make his case in court and reopen. But the harassment continues, whenever he takes books to an event or applies for a job he comes up against barriers from those who see books and learning as a threat.

“Yazidis are struggling to rebuild their lives in Sinjar, where multiple conflicts have stalled reconstruction and prevented many people from returning home. Orshina brings a ray of hope and a promise that progress is possible, even in the darkest of times,” says Faisal Al Mutar, President of Ideas Beyond Borders. “Kamiran’s desire to bring books to others is an inspiration. We need more people like him to help communities recover from the impact of conflict in Iraq and Kurdistan.”

Khalaf has used an Innovation Hub grant from Ideas Beyond Borders to secure his financial situation and purchase a laptop to establish a record-keeping system and keep track of the books he loans out. Most days, he arrives at the library around 10 am and spends the day reading and writing his own novel, pausing whenever people come in to help them find the perfect book.

He stays till around 6 and then locks up, hoping that the next day will pass smoothly without attempts to shut him down or prevent him from working. At present, he is desperately searching for a lender to rent him space on private land so that he will be out of the government’s reach. “I fear there might be at any time in the future, a government decision to make me abandon the land,” says Khalaf. “That would be a huge loss to people in Sinjar.”