Deadly Consequences: Salman Rushdie and Free Expression in the West

Where will writers and dissidents go if even the United States is no longer a safe haven for freedom of expression?

Our founder Faisal published this piece yesterday at his substack, The International Correspondent. We are cross-publishing it here to share with you our response to the heinous attack on Salman Rushdie and the lengths we are willing to go to promote and protect free speech in the Middle East.

It’s been two weeks since an armed man with an AK-47 showed up at Iranian women's rights activist and vocal dissident Masih AliNajad’s home, only one year after a kidnapping plot by Iranian intelligence operatives was formed against her.

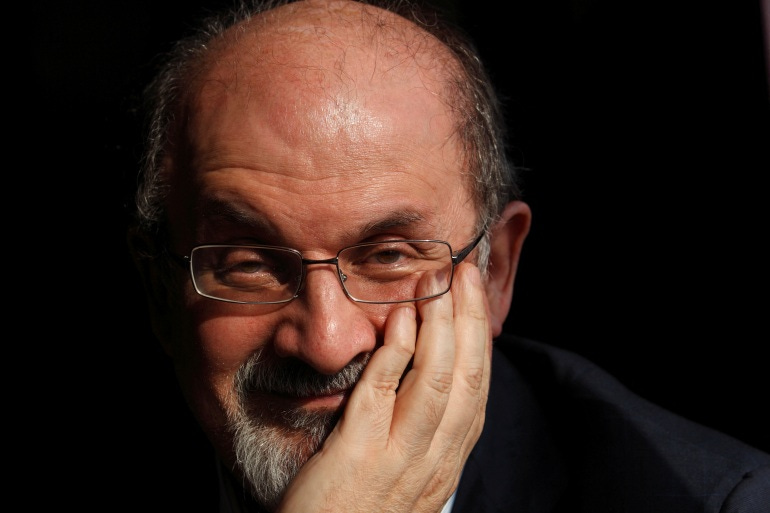

This past weekend, Salman Rushdie was stabbed as he prepared to give a lecture at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York. His attacker, like AliNajad’s, seems to have beliefs that have been heavily influenced by the Ayatollah Regime. Rushdie’s book "The Satanic Verses" has been banned in Iran since 1989, as well as in many countries across the Middle East. Even some non-Muslim majority states like Kenya and Venzuela have also banned his work.

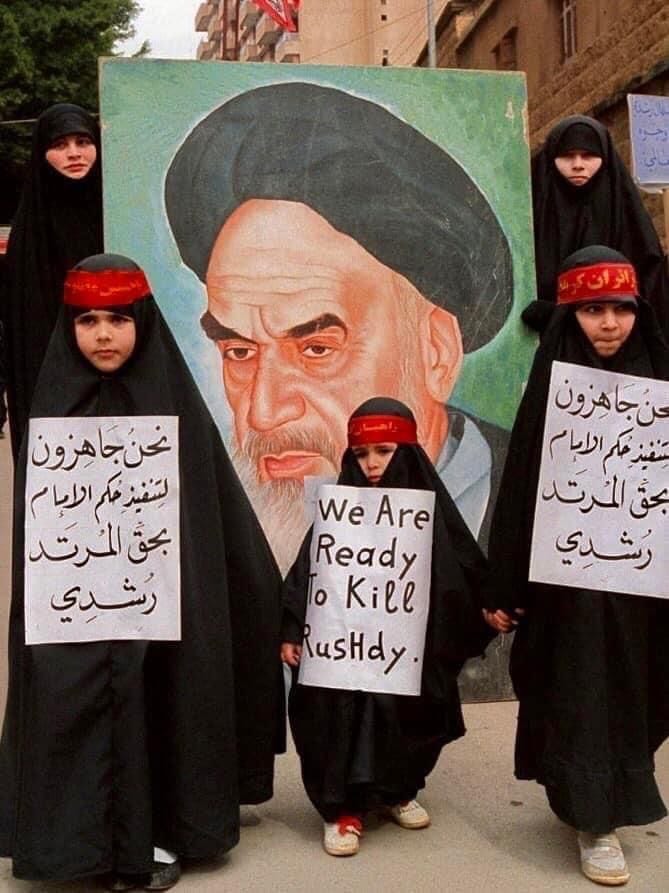

I first became familiar with Rushdie while I was living in Lebanon. In general, the free thought and Atheist movements in the west have been predominantly made up of people of a Christian or Jewish background. When I heard the name Salman Rushdie I was immediately interested to learn about him and what he had to say. One thing that struck me is that despite everything he went through, he didn’t become a reactionary atheist. It can be easily understood when people from my part of the world become bitter and militant in their intellectual pursuits given everything they have been subjected to by religious extremists. I managed to read pieces of “The Satanic Verses” in English and it didn’t take me long to realize why his work had managed to make some people in majority Muslim countries and their leaders angry. He was used as a scapegoat by those leaders to deflect from the issues at hand, something that Saddam Hussein, Khomeini, and others have championed. The biggest threat to extremism is people who think for themselves and hold a perspective not approved by the governments or the mainstream, and those angered by Rushdie’s work know that.

A few hours after Rushdie was stabbed, I called our publishing partners in the Middle East and authorized the print and distribution of more than 5,000 copies of Rushdie's books. I did this with the knowledge that it would put my life and my loved one’s lives in danger.

As I write this I am quite shaken. Not just by fear for my own life, but fear for many of the people with whom I associate who might lose their lives merely because of words and ideas. I am someone who is very openly critical of extremism and attacks on those who’s ideas frighten the regime. It is agonizing knowing that neither my organization nor I have the power to defend those who might be put on a death list or even killed for being associated with the “wrong” sorts of ideas. One publisher who refused to collaborate in the distribution of Rushdie’s books told me that he is not only afraid that his store might be attacked, but that his children might be killed. A group in Lebanon mentioned that they would like to help anonymously without attaching their name to the books. They are afraid their organization will be denied registration by the authorities for being associated with an author with a fatwa on his head like Rushdie. Even with all the risk I and those I hold dear are shouldering, I refuse to let this go or stop our work. It is more important now than ever.

I wish I was exaggerating or overstating the potentially deadly consequences for those who engage in this work. By standing firmly in opposition to ideological terrorists we all have a target on our backs. I must take these consequences into account in my everyday decisions and it is far from easy. Making these choices while running my organization, Ideas Beyond Borders, is something I really struggle with. People’s lives are at stake. I will not allow the partnerships we have worked tirelessly to build in the region end because I stand for freedom of expression. Sometimes people tell me, “I wish I had your job.” and I can’t help but laugh. I assure them that no, they don’t.

What scares me the most is that even in the West the room for freedom of expression is constantly shrinking. My initiative to End Banned Books has been chronicling the encroaching censorship of authoritarians around the world, they’re gaining territory almost everywhere. Both the attacks on Rushdie and AliNajad happened in my home state of New York, and I expect that other states and countries are not much safer. The United States, once a beacon for free speech, is becoming increasingly hostile to those who wish to speak without self-censorship and in some cases physical security.

Where will writers and dissidents go if even the United States is no longer a safe haven for freedom of expression? This leaves almost no place in the world for them to live, write, and think out loud safely. Instead they are faced with an impossible choice between living in hiding, or living openly with the knowledge that they could be shot or killed at any time.

This risk is something that those of us who do this work have had to come to terms with. We will probably have to look over our shoulders for the rest of our lives. Safety is not a guarantee, even in one of the supposedly freest countries in the world. This is an unavoidable side effect of our pursuing this profession and expressing our views with unabandon.

Attacks like the one on Rushdie are the logical outgrowths from a culture increasingly opposed to freedom of expression. From these seemingly harmless nonviolent means of censorship, whether in the form of banned books or speakers being silenced and disinvited, violent attacks are born. What happened to Rushdie should serve as a brutal reminder that the spread of illiberalism is not contained to college campuses in the US, or countries in the Middle East. When large swaths of the population begin to believe that words are violence, we are all in trouble. We should have seen this coming.

I try my best not to be a downer, but I am frankly growing weary and fearful for the future of free expression, not just in countries where censorship is the norm but in ones where it isn’t. We have no other choice but to fight with every last breath that we have for whatever is left of free speech principles. I hate to say that at this moment, we are losing. We are losing very badly. I will be taking a break for the next couple of weeks to regather my thoughts and my fortitude. Upon my return, I will get back to work defending critical thinking and freedom and other values I hold dear. The only way to combat bad ideas is by spreading better ones, making the inaccessible accessible, and giving people the choice to think for themselves.