Mobile Libraries Bring Books and Hope to Afghan Children

Charmaghz provides safe spaces to read, think and question for thousands of children living under Taliban rule.

Growing up in Afghanistan, Freshta Karim never had access to libraries. “I was probably 16 or 17 when I read a novel for the first time,” the Oxford graduate says. After securing scholarships to study at prestigious institutions abroad, she was struck by the contrast with life for her peers back in Afghanistan, where books remained out of reach for many young people. “War has robbed us of many little pleasures of childhood, including having access to libraries,” she says.

Returning to Kabul, she was determined to bring books to more Afghan children and set about transforming a second-hand public bus into a brightly painted library. “I wanted it to be different for our next generation. I wanted them to have a space to read, to think, to ask questions and to feel empowered and heard.”

It was a beautiful snowy day in Kabul when the mobile library set off, laden with books and games. That was February 2018 and since then Karim’s organization Charmaghz has grown to include 16 mobile libraries and a staff of 55 people. The remit has expanded too, from offering a space for critical thinking, which Karim’s generation lacked, to addressing the literacy poverty and mental health problems that are widespread among Afghan children. “We can’t expect children to learn when their mental health and emotional needs are not addressed,” Karim says.

Nor, she continues, can they be expected to learn on empty stomachs but with 97 percent of the population at risk of falling below the poverty line, huge numbers of children are under-nourished, affecting their physical development and learning capacity. Poverty in the country also means more child labor and child marriage, both of which are widespread in Afghanistan. “I know that our work is needed more than ever. Education is my non-violent approach,” Karim says.

The Taliban takeover last August only reinforced her resolve but the impact on Charmaghz has been devastating. Previously, the organization’s libraries were funded by Afghan businesses but the economic crisis meant the private sector withdrew its support. For two months, she was unable to pay staff salaries and the worry kept her up at night. “It felt like a personal failure as the director of the organization, but my colleagues showed huge resistance and everyone kept working until we found some funding,” she says.

This included an Innovation Hub grant from Ideas Beyond Borders which is supporting the running cost of a small van library serving around 100 children a day. The Charmaghz team is now working to secure long-term funding of around USD $150,000 to keep the libraries running into 2024. “Charmaghz is giving Afghan school children hope that a way will always be found to continue reading and learning, even in the darkest of times, says Faisal Saeed Al Mutar, Founder and President of Ideas Beyond Borders. “The mobile libraries represent the perseverance of knowledge under Taliban rule and reinforce the diversity of ideas that the group seeks to crush.”

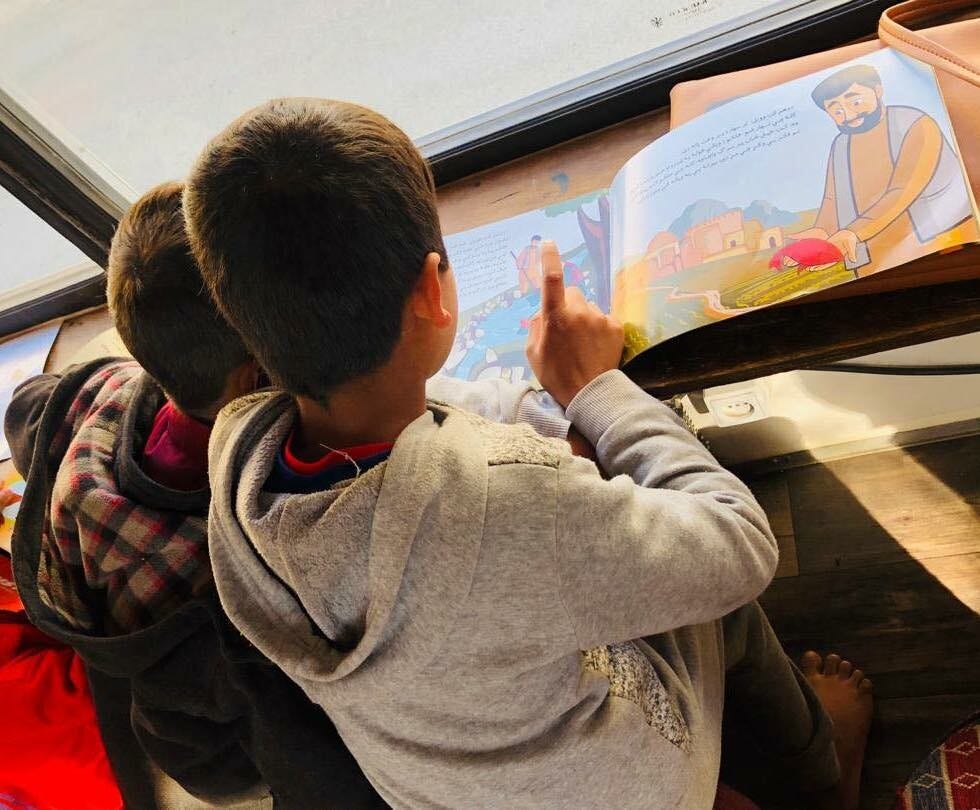

The next problem for Charmaghz was how to secure Taliban permission to operate the libraries, which attract around 2000 visits a day from both boys and girls. The children never want to leave the libraries and always request additional books so there was huge pressure to get them open again quickly, Karim says. It took Charmaghz deputy director Barakati two months of visiting the Taliban’s Ministry of Education every day to secure permission to reopen the libraries.

Now, they operate with the Taliban’s knowledge, and some of the Taliban soldiers even come to the library to read books though others have insulted staff members and, on occasion, been violent. Karim worries a lot about the impact of the Taliban ban on secondary education for girls, and what it will mean for all children in the future. “Boys are learning that it’s normal for girls not to attend school – this mindset may have horrific consequences for girls’ and women’s rights for decades to come,” she says.

Meanwhile, school standards in Afghanistan are slipping under a Taliban government that has neither expertise nor experience in managing the education sector. The libraries are “not a magical solution” to the substantial challenges Afghan children face, Karim says, but they do offer a place where they can “improve their critical thinking skills, ask questions and as a result imagine a world beyond war, then hopefully create it when they grow up.”

For further details on Charmaghz, please contact Freshta Karim on: freshta.karim@charmaghz.org