Money, Sex, Revenge: The Forces Driving Online Violence in Kurdistan.

Dr Karzan Mohammed is uncovering a network of predators targeting women, girls and young boys in Kurdistan.

The results of the research were horrifying. The abuse hadn’t just increased, it had jumped six times in three years, confirming Dr. Karzan Mohammed’s fears of an online crime network targeting women in Kurdistan. Each story was more devastating than the last. Young girls, some of them children, are targeted by sexual predators online, tricked into handing over compromising photos then blackmailed for money or sex, or sometimes as a form of punishment and revenge.

When they couldn’t pay, their pictures were shared with groups on social media, circulated among hundreds or even thousands of followers, waiting for the next victim to go viral. “It has happened to so many girls, and we’ve seen several instances of suicide in recent years because of the shame and threat from their families,” says Mohammed, the founder of the Education and Community Health Organization (ECHO).

His team has spent the last eighteen months gathering evidence to call for a change in the laws surrounding gender-based violence to include cybercrime and online harassment. In September 2021, they took their findings to the Kurdistan Parliament. They met with a positive response from ministers who agreed to revise the country’s 2011 law on gender-based violence to incorporate measures against online crime. “We presented them with robust research so nobody can argue that this isn’t going on,” says Mohammed, who is calling for robust legal protections and a dedicated cyber crimes police unit to prevent the problem from spiraling further out of control.

Mohammed, who is also the general director at Salahaddin University Research Center, is well-connected. His access to government department data and local authorities secures him the information needed to gauge the true extent of online violence against women and girls in Kurdistan. What he and his team have discovered is disturbing. Women, girls and young boys are being systematically targeted by organized groups using blackmail to extort money or sexual favors via platforms including Snapchat, Facebook, Whatsapp and Telegram.

“They approach the victims in different ways and later, they use them to get to more victims. Once you are in their game you have to bring in more people to get out,” he says. In desperation, some victims feel forced to share photos of their friends to satiate their abuser. Others sink into despair and resort to self-harm, or live in fear of the consequences if their family finds out. As a recent report titled Online Violence Towards Women in Iraq states, “sexual defamation has dangerous consequences, especially for women and girls who are at risk of “honor killings.”

Until recently, the perpetrators of online violence were typically from other countries in the region, but the last five years have seen a marked rise in local groups targeting women in Kurdistan and Iraq.

Mohammed points to a Kurdistan-based group called CTS, known for publishing pictures and videos of women in bulk. Led by an individual named Govand, the group exploits its victims in multiple ways, which include humiliating punishments, such as forcing them to come online and apologize to the group’s leader in a live stream. According to a report in Rudaw, a number of victims were charged $5,000 to keep their photos private, but in some cases, they were published anyway.

According to Mohammed’s findings, other local groups have copied this pattern of exploitation, with the rate of reported online abuse doubling every year. “Some groups do it for money and some for sexual gratification. Others use it as a form of punishment and power; they say you have disobeyed God, so now we will expose you to the whole community. And you don’t know which one you will fall prey to,” he says.

Usually, the women and girls targeted are unaware of the risks they face in the digital sphere. Perpetrators typically start a conversation on social media, often spending months gaining their confidence and cultivating a relationship online. When they eventually persuade their victim to share compromising photos or videos, the blackmail starts. “The community sees these women as guilty… online violence is a major cause of depression. You cannot speak out, you cannot tell your family or friends. It’s a very lonely place,” Mohammed adds.

Several people working with Govan’s group have been arrested, but the ringleader remains at large and is believed to have gone abroad. Meanwhile, the group remains active with around 35000 followers on their Telegram channel and a constant stream of pictures and videos exposing new victims to humiliation and despair.

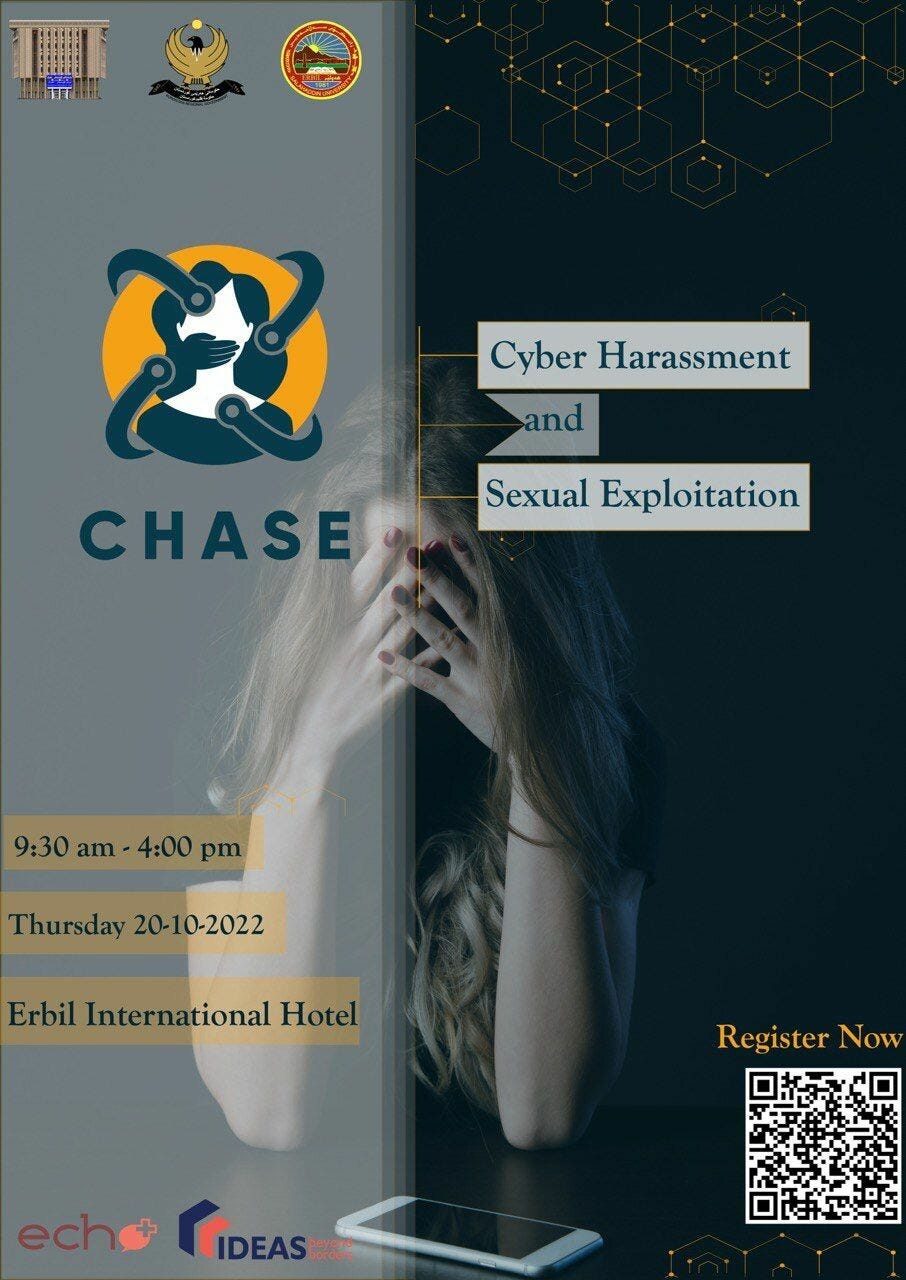

In October, ECHO hosted the Cyber Harassment and Sexual Exploitation CHASE symposium funded by an Innovation Hub grant from Ideas Beyond Borders to tackle online crimes against women in Kurdistan. “We wanted to send out a message to victims that the law is with them, parliament is with them – there are people working to address these issues,” Mohammed says.

Currently, the amendment, which adds online violence and other forms of abuse to the list of violations against women, has been delayed due to a dispute around sections designed to prevent marital rape and forced marital sex. At the symposium, ECHO announced a large-scale campaign with academics and institutions to educate the public and advocate for the amendment to pass in its entirety. In addition, Kurdistan’s Ministry of Education agreed for the first time to include harassment and sexual exploitation in the national curriculum so that children aged 14 to 17 are aware of the risks and impact of these practices online.

“Sexual exploitation is a major issue, especially the direct targeting of Yazidis and widows who lost their husbands due to decades of war,” says Faisal Saeed Al Mutar, founder and president of Ideas Beyond Borders. “We hope our grant help empower a new generation to avoid exploitation by bad actors.”

In the long term, Mohammed says, the emphasis needs to be on educating and empowering women and girls to ensure they are less vulnerable to these practices. “Most of the victims are poorly educated and are not free to leave the house,” Mohammed says. He points to the high rate of unemployment among youth in the region. “They stay at home or sit in cafes smoking shisha and spend hours on their mobile. You need to empower, educate and create opportunities for everyone. It’s multi-faceted.”