Paper With a Purpose

Basoz Mohammed-Amin is tackling paper waste in Kurdistan with exquisite stationery made by hand

Every time Basoz Mohammed-Amin passed the rubbish bins at college, her frustration grew. They were always overflowing with paper, some of it hardly used, particularly in the art department where she studied. “People would draw a line on the paper then chuck it. The waste was terrible,” she says.

There has long been a culture of re-use in the Kurdish city of Sulaymaniyah, where Mohammed-Amin lives, but few people recycle items regarded as rubbish. “People care about health and the environment, but they don’t make the connection with recycling paper,” says the 24-year-old. “People have so many problems they forget about recycling.”

She decided to do something about it. Her first step was to educate herself on the process of recycling paper. With no local resources to help her, she looked online, learning through YouTube videos and researching different methods around the world. “Most other countries have recycling, but here it’s new because we don’t have the facilities,” she says.

Unable to source the paper pulping machine she needed, Mohammed-Amin worked with a local engineer to create one from scratch. After exploring various approaches, she embraced a traditional process that uses basic tools and takes several days to complete by hand.

The result is thick-cut paper with a rustic, textured feel that is already proving popular with her growing clientele of artists, students, and writers. “They like the antique vibe,” says Mohammed-Amin, who decided to continue with the labor-intensive traditional method when she saw the beautiful results.

The first step, she says, is to gather waste paper from offices, universities, schools, and other sites. She sorts it by color and quality before shredding and then pulping it, which usually takes one to two days. She then uses a frame to shape the pulp and press out the water by hand. This part is important because it determines the quality of the paper, allowing it to bind properly when more of the water is removed. The paper is then placed in a drying machine or outside to dry in the open air for up to 12 hours.

There are faster and more efficient ways of recycling paper, but Mohammed-Amin is committed to the traditional method and the results it yields. She also enjoys the process. “It’s physically taxing and takes a long time, but it’s also a joyful process for me. I forget about myself and enjoy the work.”

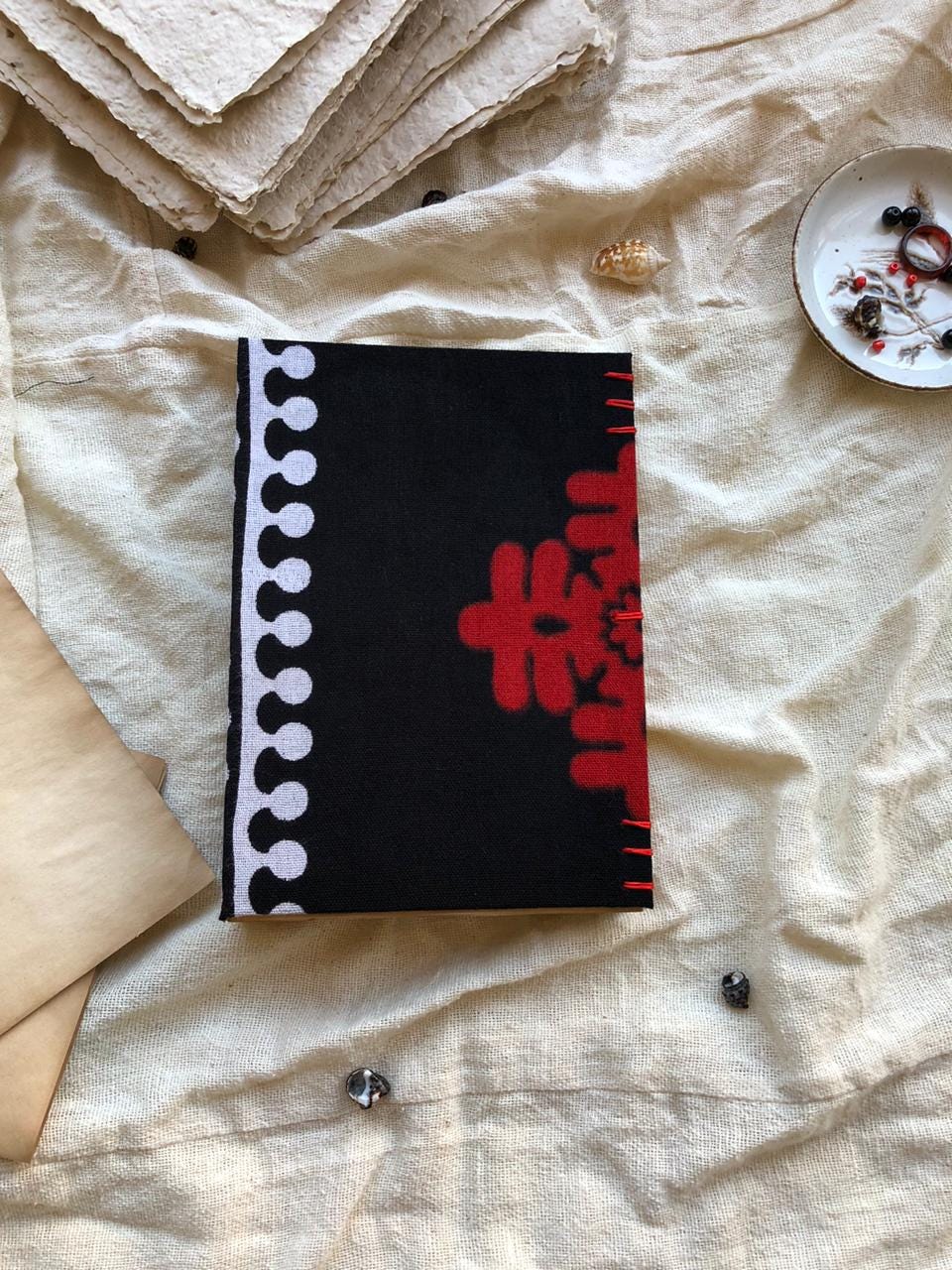

When the paper is ready, she turns it into notebooks, sketchbooks, and envelopes. One notebook requires 30 pieces of paper, which she binds by hand using a needle and thread. Her own designs adorn the covers, featuring traditional Kurdish tools with texts explaining their use and the recycling process the paper has undergone.

“New generations should be aware of Kurdish customs and traditions. These illustrations help them to understand their heritage,” she explains.

Mohammed-Amin is using an Innovation Hub grant to purchase tools that will make the recycling process easier without compromising the quality of the products she produces. She hopes to be able to reduce the price of her paper, which currently costs more than standard sheets so that more people can see and appreciate the value of recycling. “I feel I have a responsibility to make people more aware,” says Mohammed-Amin, who believes word is spreading as her network expands.

“It's going slowly, but people are starting to make the connection between the paper products they use and the health of their surroundings,” she says.

This article was written by Olivia Cuthbert.