Schooling for Street Children in Afghanistan

Early morning classes at Hero Junior Academy give children a chance to learn while new libraries bring books to rural areas across Afghanistan.

Mustafa, 10, and Rustam, 13, have dropped by their classroom to pick up a football. Every Friday, they get together with 10 other boys to play a game of six-a-side at a nearby park in Kabul, Afghanistan. The ball tucked proudly under Mustafa’s arm is brand new. “They were wrapping up cloths and sheets and making a ball out of them, so I promised I would get them a proper one,” says Ahmad Jawid Karimyan, who runs an informal school for these boys during the week.

Lessons last three hours a day, which is all the children can spare. They study from 7 am to 10 am, then work till seven or eight in the evening, polishing shoes, washing cars and selling plastic bags on the streets. “Some of them are beggars. They need this income to survive,” says Karimyan, who set up Hero Junior Academy in 2022 to provide access to learning for Afghan street children missing out on school. “The goal was to bring kids without parents or guardians, who are doing child labor, and give them an education with the tools to learn,” he adds.

Initially, many refused to attend because they need the time to earn, so Karimyan offered to provide breakfast, and they agreed. Supported by an Innovation Hub grant from Ideas Beyond Borders, he hired teachers to run classes in Maths, English and Dari, the form of Persian spoken in Afghanistan. This is Mustafa and Rustam’s favorite class because, like many of their classmates, they are unable to read and write. “We want to be able to read storybooks,” Mustafa says before heading off to the game.

Over time, the emphasis on breakfast has subsided as the boy’s appetite for learning increases. “Even on days when we run out of gas to cook food, they are happy just to eat bread and learn,” Karimyan says. Most hadn’t considered education before joining Hero Junior Academy, which launched earlier this year. “Many of them thought they would be polishing shoes for the rest of their lives. That was how they saw the world and their place in it,” says Karimyan.

He knows from experience what that vision of the future feels like. As a child, he missed out on school to work on the streets, selling water and ferrying goods in exchange for small sums. “I really loved reading books, but I had no money to buy them, and there were many others like me,” he says.

When the Taliban seized power in August 2021, Afghanistan suffered an economic collapse that pushed almost the entire population into poverty. Today, the streets of Kabul are lined with beggars, many of them children whose families are unable to buy food amid soaring prices. Outside the capital, the situation is even worse as rural areas that have been sidelined for years fall deeper into poverty.

Last year, Karimyan launched a library in Ghorband, a district of Parwan Province that sits in the foothills of the Hindu Kush mountain range, about two hours by car from Kabul. Life in this part of Afghanistan was hard even before the economic turmoil of the past two years. Recent decades have seen very little investment in Ghorband, a rural area where fertile plains produce a rich crop of almonds, apples, grapes, apricots and peaches, fed by meltwater running off the Shibar Pass.

In photographs, it looks idyllic, with the clear waters of the Ghorband River winding through a leafy valley framed by snow-capped mountains reaching toward blue skies. But the picture is very different in the towns and villages of Parwan, where lack of investment has fuelled illiteracy and unemployment, leaving more than half the population aged seven or older without any formal education.

“Access to education is bad across many rural areas in Afghanistan, and Ghorband is no exception,” Karimyan says. “During the sixties and seventies, they would bring portable cinemas and books fairs. They even built a school. But during the republic, all they did was modernize the roads.”

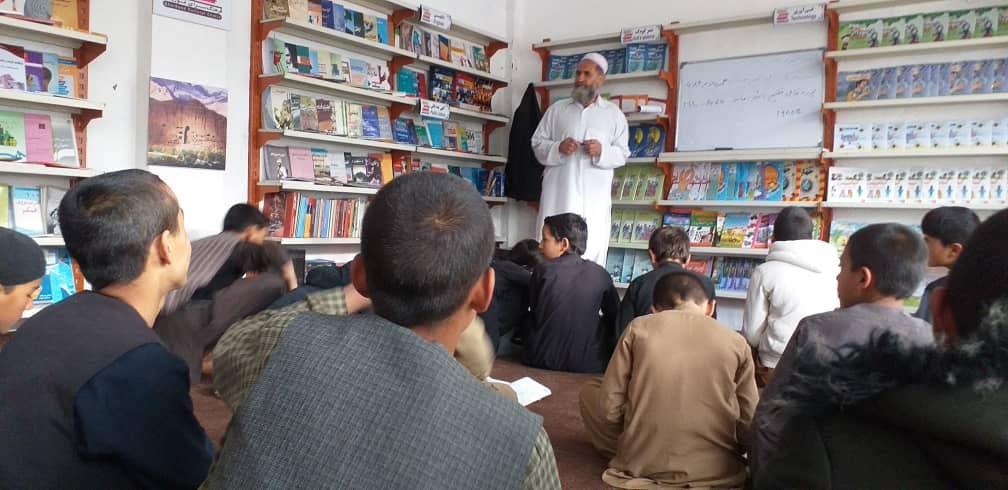

The library was the first to open in Ghorband in over 50 years, and he has since opened others in three more provinces – Badakhshan, Takhar and Paktia. “At first, people were confused by the concept, but once we explained how the libraries work, we saw how eager they were to use the books and learn,” says Karimyan.

Ghorband Library, which was funded by an earlier Innovation Hub grant from Ideas Beyond Borders, now houses around 1500 books and hosts over 100 visitors a day. Many take books home to their sisters, wives and mothers, who can’t come in person due to current restrictions on women in Afghanistan.

“I wanted to create a space for the kids who work on the streets to show them that this, in Ghorband, is not the whole world. Now I am at a point where I cannot stop what I’m doing; people around me are interested, their families are interested,” says Karimyan. “When I go there and see their faces, their enthusiasm to learn or study, their progress, it compels me to work harder for them because I see that this is a necessity now.”

His next step is to secure funding to purchase a few computers so he can teach the children IT skills, which they are keen to learn. Watching the transformation has been remarkable, Karimyan says, and he hopes to expand the academy to other areas of Afghanistan where child labor is on the rise. “These kids thought they would be polishing shoes for the rest of their lives. That was how they saw the world and their future. Now, they have bigger dreams and a motivation to continue their education, they are hopeful,” he says.

This article was written by Olivia Cuthbert.