Spoken Word in Kurdish

Our Stories is building a library of audio books in Kurdish, celebrating different dialects with a new body of literature online

There’s a phrase used in parts of Kurdistan to describe people who went to school in Arabic-speaking communities. “They call them ‘second-hand Kurds’, because they don’t speak Kurdish ‘properly,” says Megan Kelly, pointing to a tendency for people to adjust their accents so they blend in.

Interpretations of Kurdish vary across greater Kurdistan, a region spanning four countries and cultures with multiple dialects spoken throughout. Two main languages predominate, with Kurmanji - the most widely spoken - common across Kurdish regions of Turkey and Syria, as well as parts of Iraq, while Sorani is used in Iran and across much of Iraq. Bahdini, a smaller dialect similar to Kurmanji, is spoken in Duhok, a governorate bordering Turkey and Syria.

For many Kurds, language is at the heart of a cherished Kurdish identity in a region where they have long been marginalized and forced to fight for their existence. But beneath this common cause, divisions between communities are reinforced by linguistic differences and the political affiliations they imply.

In the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI), snap judgments can be made based on a person’s dialect and accent. In the eastern city of Sulimaniye, people speak Sorani, which is often taken to mean they support the PUK, one of the major Iraqi Kurdish political parties. “If you speak Bahdini here, people might act like they don’t understand you, even if they do, because to speak Bahdini is almost inherently aligned with the KDP,” says Kelly, referring to the PUK’s major political rival in KRI.

“That’s the idea people have, whether it’s real or not, which is a real barrier for people to have conversations,” adds Kelly, who is hoping that a new literary project will help to break this down. Our Stories, launched with support from an Ideas Beyond Borders Innovation Hub grant, is producing a library of audiobooks from works published by authors across Kurdistan.

“The idea is not just to share local writing but to share local writing in local languages,” says Kelly, pointing to the lack of audiobook material available in Kurdish dialects. The project emerged from a conversation with Ramazan Manaf, a volunteer-turned-colleague who suggested that audiobooks would help local authors share their stories with a wider audience.

By building an audiobook library, Kelly and Manaf hope to tap into the wider creative community, offering work to voice actors who struggle to find opportunities in Kurdistan. “There are very few roles for Kurdish speakers in the film, so it’s about figuring out how we can support this creative community and offer more opportunities to people,” she says.

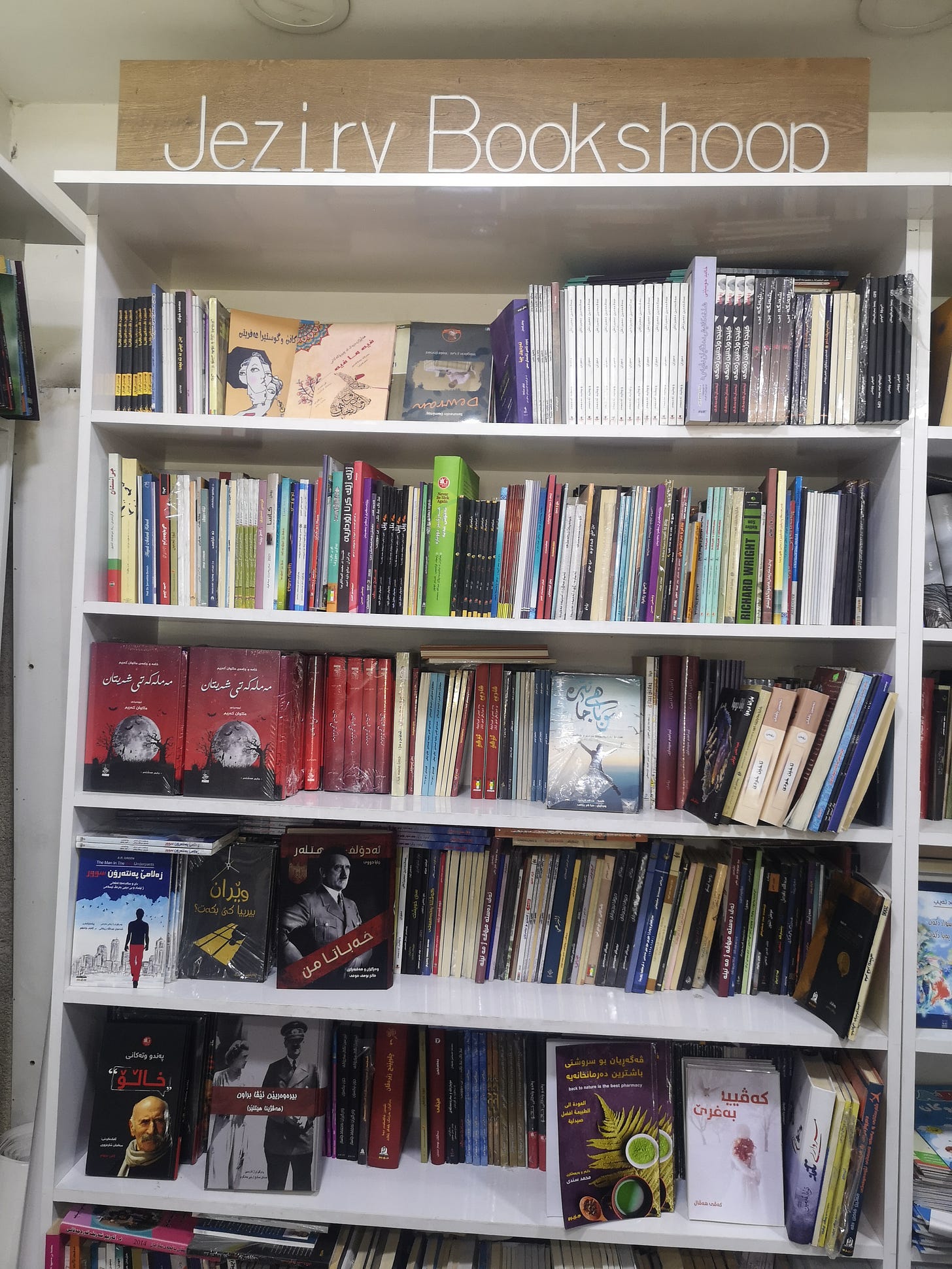

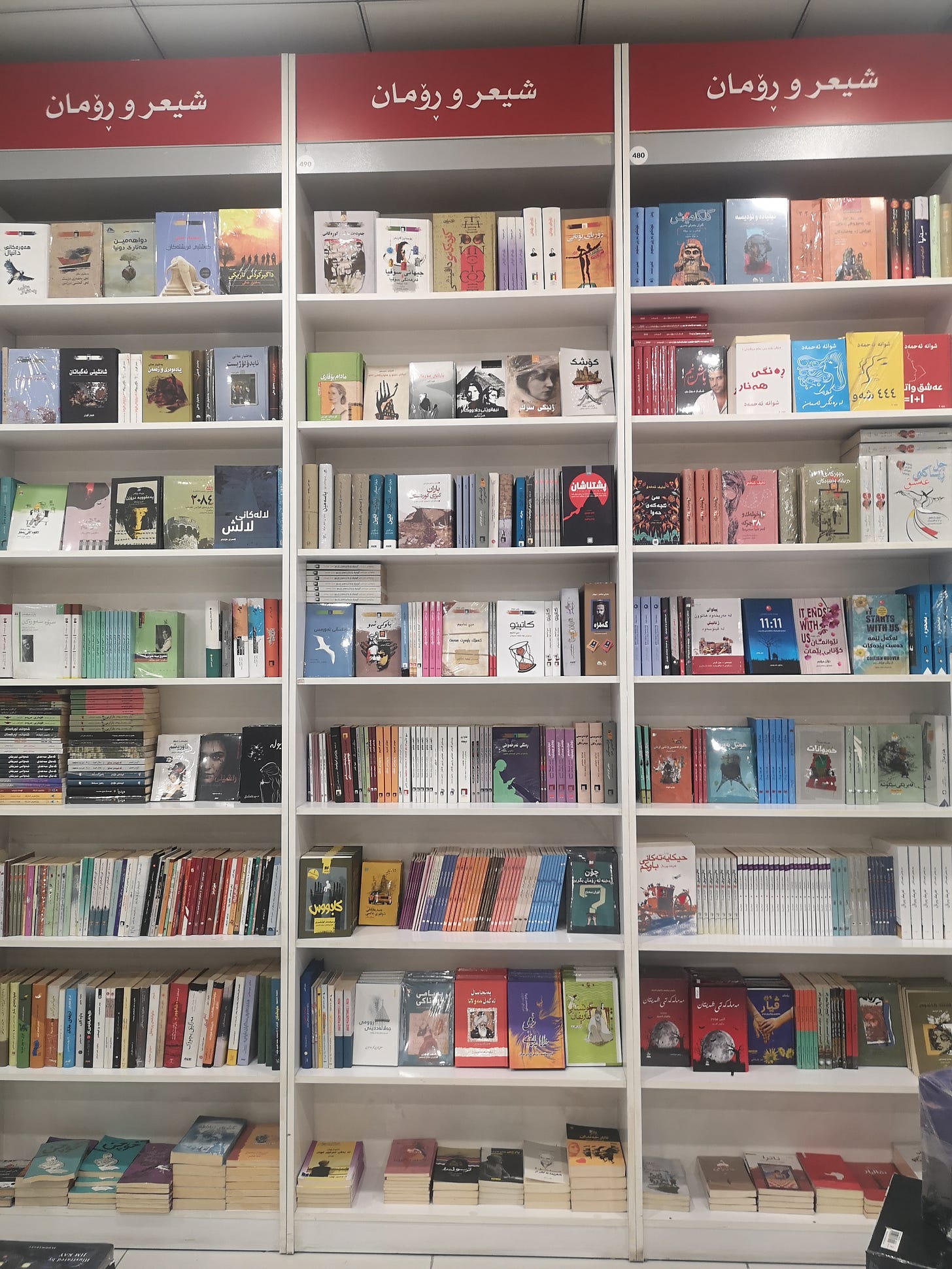

Our Stories is compiling a database of authors by contacting bookshops to find out which are their bestselling writers living in the Kurdish region. “They can write in English, Arabic or Kurdish as long as they are based here,” says Kelly, who hopes to include books in Kurmanji, Bahdini, and Sorani, as well as less-widely spoken local languages like Assyrian.

“A lot of the books available here are Western works that have been translated into Kurdish. We want to find out who’s writing here and make their work available to local audiences,” Kelly says. A lot of people in Kurdistan are interested in literature, she says, but technology has changed how people consume media; making them available in audio format is a good way to reach a wider audience.

Historical fiction is a popular genre, and there’s a particular demand for self-help books, says Kelly, which she attributes partly to the social and political challenges that characterize everyday life in Kurdistan. In a region where advocacy is difficult, and the government frequently falls short in addressing the challenges people face, books help provide coping mechanisms, she says. “If you’re going to survive these structural issues, you do have to adapt this personalized approach to dealing with it.”

Books about life under ISIS are also in high demand. Cities in KRI host a large number of displaced people from surrounding areas due to their relative stability. Duhok, which borders former ISIS-occupied Ninewa on one side, and Syria and Turkey on the other, has the highest number of refugees in the country and the second highest number of IDPs, despite its relatively small size, but all three major cities have seen significant shifts in the last decade.

“There is a curiosity to know what life was like under ISIS. Learning about it through books is a way to build understanding and empathy for displaced communities,” says Kelly.

Many of those recently displaced are Kurmanji speakers now living in Duhok, where Bahdini is the dominant dialect. Kelly’s hope is that the Our Stories audio library will widen access to Kurdish dialects for language learners who are hoping to adopt local tongues. “Audiobooks are a great way to learn behind closed doors,” she adds, pointing to the dearth of learning materials available across all Kurdish languages.

By making more materials available, she hopes a greater understanding between Kurdish speakers will help to dissolve the divisions that exist, easing integration as people and communities adapt to demographic changes.

“For a really long time, life here was focused on survival. People have lived through sanctions, genocide, war, and economic collapse. We want people to have a chance to breathe and tell their stories, in the hope that this will legitimize creative interests and let people know these are worthwhile pursuits in this culture,” she adds.

This article was written by Olivia Cuthbert.