Syrian Refugees: ‘There’s No Hope, They Just Try To Survive’

Al Caravan is bringing opportunities to Syrian refugees in Lebanon, where many families face an impossible predicament as their welcome expires.

Little changes from day to day on the farms in eastern Lebanon. Life is a long grind of 14-hour days, hard labor and just enough pay to survive. Mostly, it’s women working in these fields, many of them Syrian refugees who fled to Lebanon to wait out the war. “Before 2020, there was some hope among Syrians of returning home, but now it’s too dangerous,” says Khaldoun Al Batal, whose organization Al Caravan provides support and assistance to refugee families in Lebanon.

Research conducted by Refugee Protection Watch found that just 0.8 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon are considering returning to Syria. Many are afraid following accounts of grave human rights violations against returnees by the Syrian government, with widespread reports of torture, kidnapping and killing.

Instead, most Syrians are stuck living in Lebanon illegally, risking detention and deportation, which leaves them vulnerable to exploitation by employers who know they will work harder for less. Of the estimated 1.5 million Syrian refugees in Lebanon, more than 80 percent lack legal residency, denying them access to many basic services like health and education. “They just live day by day, they don’t have any expectations for the future, there’s no hope, they just try to survive,” says Al Batal, who left Damascus in 2012 as the fighting escalated.

In the bitter civil war that followed, President Bashar al-Assad and his regime subjected the Syrian population to immense suffering. His prisons became notorious torture chambers and hundreds were killed in chemical weapons attacks on civilian targets, for which he was widely condemned by the international community and expelled from the Arab League. Millions of Syrians fled, with an estimated 13 million people displaced, 6.7 million of whom sought shelter abroad, mostly in neighboring countries.

Now, a recent agreement among member states to welcome Syria back into the Arab League has exacerbated the predicament facing Syrian refugees, with rights groups reporting that forcible deportations have risen in Lebanon since early April. With the country at breaking point, authorities are increasingly scapegoating Syrian refugees for Lebanon’s economic woes. Anti-Syrian sentiment is never far from the surface in Lebanon, which was occupied by Syria during and after the 1975-1990 civil war, but a recent rise in racial tensions has left many Syrians feeling, once again, like there is nowhere safe to go.

Rather than risk returning to Syria, some attempt the dangerous crossing to Europe, where more than 29,000 people have died since 2014, including over 5,000 between January 2021 and October 2022 alone. “It is telling that, despite the deteriorating situation in Lebanon, many Syrian refugees feel their only option is to stay put in increasingly desperate circumstances. They deserve better support, better choices and a chance to finally feel safe,” says Faisal Al Mutar, President of Ideas Beyond Borders.

Life has always been difficult for Syrian refugees in Lebanon, but the knock-on effects of the Covid-19 pandemic, economic downturn and Beirut blast have pushed thousands of families deeper into poverty. The impacts have been felt acutely among refugee communities, with an estimated 90 percent of Syrian refugee households now in extreme poverty, up from 55 percent in early 2019.

According to the UN, these households live on roughly $36 a month, less than half the minimum wage in Lebanon, where steep inflation and spiraling food prices mean many can hardly afford to buy bread. In the daily struggle for survival, there is little opportunity to fight for a better life. An estimated 30 percent of school-age (6-17) refugee children have never been to school, shut out by the high cost of transportation, expensive school supplies and limited places in public schools.

Some accommodate Syrian children in a second shift, but many simply do not attend school. “Those that do go get the afternoon shift when teachers are tired,” Al Batal says.

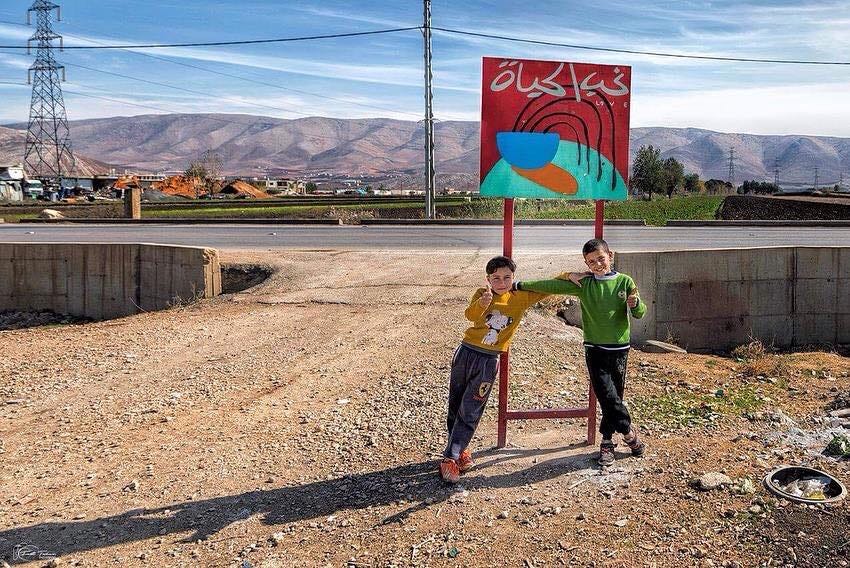

This is particularly true of rural areas, where funding is scarce, and school closures in recent years have left many communities with limited access to education. Using an Innovation Hub grant from Ideas Beyond Borders, Al Batal is planning to provide awareness activities around violence and peacebuilding, informal education for ages 8 to 18, and art sessions to Syrians living in the remote Bekaa and Akkar regions. “We want to close the gap in opportunities between the countryside and the city,” he says.

Al Batal, who has lived in Lebanon for seven years, sees this as an investment not just in Syrian communities, but in the future of Lebanon and the hope that future generations will lift the country out of crisis. “If children lack opportunities to grow and develop in a positive way, they are more at risk from turning to negative survival solutions,” he says, pointing to the exploitation of vulnerable communities by drug gangs and militias operating in these areas.

Al Caravan also runs sessions that include children from vulnerable Lebanese families as well as refugee communities designed to break down barriers and support social cohesion. “Some Lebanese feel the Syrians get all the work, money from the UN and sympathy in the media…we need activities on this level to avoid conflict and teach them how they can collaborate together as humans to create better lives.”